The annual Vancouver city directories for 823 Jackson Avenue sometimes list the Reverend, Minister or Pastor. This was especially true in the early years of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, in the 1920s and 1930s, when ministers would come from the United States and would stay for several years at a time. At some point, however, the turnover of ministers increased and the directories would rarely list a presiding minister. Nora Hendrix notes in an interview from 1977 that: “… then after six years we commenced getting different preachers every year pretty well.” (Opening Doors, Marlatt and Itter, 1979).

From 1942 to 1951 the city directories list a minister in only a single year, 1944: Rev. Theodore R. Jones. Rev. Jones was born in 1901 in Arkansas, the grandson of a Methodist minister. He graduated from Flake University in Nashville Tennessee, and from Livingstone College, Hood Theological Seminary in Salisbury, North Carolina. Livingstone College and Hood Theological Seminary are affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, technically a different denomination than the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Rev. Jones taught for four years in Africa, was ordained in 1932 and then spent three years in South America and the Virgin Islands. Rev. Jones came to Vancouver around September, 1943 and it’s not clear how long he remained the pastor of the Fountain Chapel.

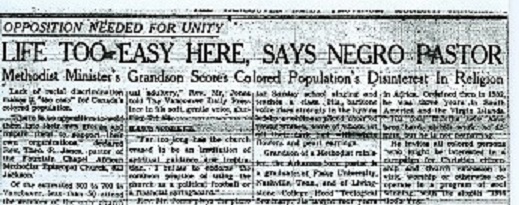

In an article for the Province dated January 17, 1944, entitled “Life Too Easy Here, Says Negro Pastor” (pictured), Rev. Jones gives his opinion that the “lack of racial discrimination makes it too easy” for black people in Canada. He also comments that: “The colored population of Vancouver is in a state of spiritual adultery,” and that “of the estimated 500 or 700 [black people] in Vancouver, less than 50 attend the service of the only church for colored people here.”

Of course there was some racial discrimination in Vancouver and much of it was subtle. Adam Rudder discusses this in detail in his Master’s Thesis: “A Black Community in Vancouver?: A History of Invisibility” (University of Victoria, 2004). However such discrimination did not prevent a significant degree of mobility and Rev. Jones characterization of “spiritual adultery” reinforces the notion that many black people no longer lived in the neighborhood and were comfortable attending services in other churches. Rudder notes that: “… it seems certain that by the end of the 1950s black people had moved from Strathcona and scattered into the greater Vancouver area … families chose to move outside of the lower socio-economic area of Strathcona and into more middle class neighborhoods … when black people were able to get better jobs, they began to buy houses in other areas of the city.”

Also, Rev. Mac Elrod, who attempted to restart the AME congregation in 1969 found that the original congregation had largely moved out of the neighborhood and were attending services in other churches. Rudder concludes that “Whether it was convenience, dissatisfaction with the AME church or spiritual adultery that influenced black people to attend church in their new neighborhoods remains a question for debate. Unfortunately for the church, the migration of wealthier black people out of the Strathcona area also meant the loss of some of their key members.”

Thus, the decline of the AME congregation at 823 Jackson Avenue can at least in part be attributed to the upward mobility of the original congregation. Many had left Strathcona not because they had to but because they could (i.e. on their own terms). Purvey and Belshaw note that “Strathcona is Vancouver’s doorstep, the community that welcomes newcomers, … of all Vancouver’s communities, it was the most diverse, … [with] newcomers on the way up and out, and Vancouverites on the way down.” (Vancouver Noir 1930-1960, 2011)