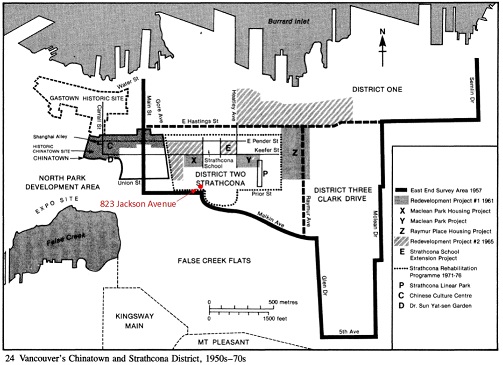

Strathcona, where 823 Jackson Avenue is located, is a neighborhood just east of Vancouver’s Chinatown. Strathcona came under pressure in the 1950’s and 1960’s under Vancouver’s slum clearance and urban renewal programs. Eventually several city blocks in Strathcona were obliterated before the program came to an end. Shown above is Figure 24 from David Lai’s definitive book “Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada” [Lai, 1988].

The concept of urban renewal and slum clearance in Strathcona began as early as 1950, when Dr. Leonard Marsh proposed in a report a major redevelopment scheme for Strathcona. Dr. Marsh’s report noted that a majority of the properties in Strathcona were dilapidated and he called for the acquisition and clearance of such properties and replacement with rental housing. In 1958 the Vancouver City Council approved a redevelopment plan that called for the demolition of nearly all old buildings in Strathcona. Because of this, regular public works maintenance in Strathcona ceased, property values in the neighborhood were frozen and no redevelopment permits were issued to property owners.

Vancouver’s urban renewal program forced owners to sell their properties at a negotiated price, which ranged from $6,000 to $8,000 and houses were expropriated if an owner refused to sell. Lai notes that “Most homeowners complained that the price offered was insufficient to purchase houses elsewhere in the city. However, within a year, over six city blocks in Strathcona had been appropriated and their structures, including some historic Chinese ‘tong houses’ such as the Hing Mee Society house, were demolished to provide sites for the extension of the Maclean Park Housing Project, the replacement of Maclean Park, and construction of the 376-unit Raymur Place Housing Project. About 300 Chinese residents were forced to move, some of whom were very bitter about the clearance, arguing that the social impact on the community had not been considered.” [Lai, p. 128]

Nevertheless, the city persisted and in December 1962, Vancouver City Council announced Redevelopment Project No. 2, which would involve the acquisition and clearance of nearly thirty acres of land and the displacement of about 2,300 people. The project included five city blocks in Strathcona and would displace 770 persons, mostly Chinese, in order to provide sites for public and private housing, and for the expansion of Strathcona School. Various Chinese associations immediately protested against the project, which was criticized as being “unwise, too ambitious and without regard for the human element.” They argued that apartments were unsuitable for the Chinese family system, in which members of several different generations lived together. The expropriation and clearance program under Project No. 2 would force Chinese families to move out of Chinatown and would destroy four Chinese schools and scores of Chinese fraternal associations. [Lai, p. 129]

Luckily the structure at 823 Jackson Avenue avoided this fate. This was particularly fortunate because by this time the AME congregation has dispersed and the building was little used and in poor condition. The building was listed as being vacant in 1964 and 1965 and starting in 1966 it was listed as being occupied by a different denomination, the AME Zion church, which did not own the building. Mac Elrod, the AME minister who took back the building in 1969, reported that when he arrived the building was being used by AME Zion “not holding service but using it as a hostel for the homeless” [Rudder, 2004]

Vancouver’s Urban Renewal Project Numbers 1 and 2 had displaced about 1,000 people, of whom more than half were Chinese. Mr. Lai notes that “In the implementation of these two projects, attention was paid only to physical improvement of Strathcona District; no consideration was given to the social problems of residents. A survey conducted by United Community Services revealed that the reaction of the people, particularly the Italians, whose homes were to be destroyed, bordered on panic. Some people who had been moved into Maclean Park Housing Project led solitary, isolated lives and had little contact with the area’s recreational agencies. The survey also revealed that most people in the district, particularly Chinese residents, would have liked to own their own homes, continue to raise home-grown vegetables and flowers, and maintain a sense of security by living close to Chinatown.” [Lai, p. 130]

Undeterred, in the summer of 1965, Vancouver’s Planning Department started to work on the details of the third and final stage of clearance of remaining housing in Strathcona and relocation of its 3,000 residents. This clearance program was part of Urban Renewal Scheme No. 3, which covered five subareas: Strathcona, False Creek Flats, Clark Drive, Kingsway, Main, and Mount Pleasant. [Lai, p. 130]

Opposition efforts came to a head in December 1968, when about 600 people came to a meeting at which the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) was formed. Lai notes that “They sent briefs and petitions to City Council, demanding the right to continue to live in the Strathcona area and suggesting that Council should lend residents money to improve their homes instead of buying them and tearing them down. Residents were not against physical improvements in Strathcona but they disapproved of how the city had handled the whole process. Urban renewal had created more social problems than it had solved; it had resulted in unaccountable psychological and socioeconomic costs, such as the anxiety and uncertainty of the residents, disruption of a familiar environment, financial loss resulting from inadequate compensation, and destruction of many structures of high heritage value. In his study of displaced Chinese families, Richard Nann found that ‘reactions of anger, bitterness, frustration, resignation and relief were constantly encountered by the researchers’; in some instances, relocation meant major disruption and frustration of life achievements and aspirations. Some Chinese people perceived the redevelopment programs as an attempt by the government to remove Chinese families from valuable real estate.” [Lai, p. 131]

The organization of SPOTA and their vocal opposition was the beginning of the end of the urban renewal programs. In early 1969, Paul Hellyer, the Minister of Housing, froze federal funding for all urban renewal projects other than those currently implemented. This signaled a change in the perspective of the federal government . Meanwhile, SPOTA had become one of the strongest community action groups in Vancouver. It continued to pressure Council to abandon its urban renewal programs. In August 1969, the Minster of Housing announced that the renewal scheme planned for Strathcona area would not proceed as originally planned.